Vaster than Empires and More Slow

It was, of course, Andrew Marvell, not me, who wrote 'vaster than empires and more slow', but the line kept coming into my mind as I was thinking about the two books in this month's post. Some time or other, probably at school, I was told that the Romans came to Britain, stayed a few hundred years, and then left when the Empire started to crumble and they had to get back to defend Rome against marauding barbarians. After that, life in Britain more or less reverted to the uncivilised state that had existed before the Romans arrived, and everything went dark until the Normans came. Rosemary Sutcliff likes to shine a light on those supposed 'dark ages', though in her use of the image of 'lantern bearers' carrying the light of Roman (and Christian) civilisation forward after the Romans left, she is, in a way, perpetuating the idea of an age of darkness. But that doesn't prevent this being a brilliant book.

Sutcliff describes how, while making toast for breakfast one morning, a thought struck her:

"The thought (and I swear my brain doesn’t usually work this way, by spontaneous combustion) was 'Yes but the Legions weren’t just an occupation force, they’d been here for four hundred and fifty years!'

Four hundred and fifty years; roughly the space of time that lies between ourselves and the early Tudors; and the Roman Authorities had no feeling against interbreeding with the native population . . . British blood must have been quite noticeably laced with that of the Legions, and probably few Legionaries could not boast at least a British grandmother.'"

This was the origin of The Lantern Bearers, the 1959 winner of the Carnegie Medal. The book is the final volume of the trilogy which began with The Eagle of the Ninth and continued with The Silver Branch. For me, The Lantern Bearers is the best of the three, and is one of Sutcliff's finest achievements. It's not too much of a spoiler to say that the story concerns Aquila, a Romano-British legionary who decides at the last moment to stay in Britain with his family as the last Roman ships sail away. In a Saxon raid his family are brutally killed and his sister carried off. He's left tied to a stake for wolves to eat, but another Saxon takes him as a slave. For most of the book, he is a bitter, angry man, the more so after he tries to rescue his sister and finds that she has adapted to her new situation, has a child, and doesn't want to be rescued.

|

| Illustration by Charles Keeping |

Eventually Aquila rises high in the company of Ambrosius Aurelianus, who is credited by Gildas, a (real) monk writing a century after the event, with winning a decisive battle against the Saxons. Ambrosius is the only person from the fifth century who Gildas mentions by name, so Rosemary Sutcliff had a wide field for invention, and she manages to link up Aquila's story with 'the war leader whose medieval romance turned into King Arthur.' But what resonates most for me is the feeling of a massive historical change, as a way of life that has been more or less stable for more than four centuries came to an end.

It is an amazing thing about humanity that we never seem to learn the lessons of history. Everything changes - the Roman Empire, the British Empire, the European Community . . . Everything seems to be going along just fine then along comes a new virus, or the Black Death, or the Goths, Visigoths and Vandals, the Saxons and Danes. In the 1970s it was hard to imagine that the Berlin Wall would ever come down. In the third century CE it must have been impossible to imagine life without the Roman Empire. The fact is, we have no clue what might happen next, and this idea, perhaps surprisingly, makes an appearance in the 1960 Carnegie winner, The Making of Man, by I W Cornwall and M Maitland Howard.

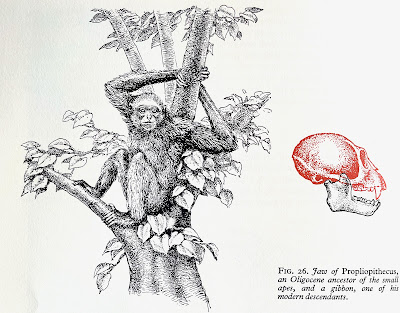

This book was (slightly shockingly) the last non-fiction title to win the award, and is also the best. It is a history of the evolution of man (no trouble with terminology in 1960). It's clearly written, well-organised and illustrated ingeniously in two colours, with black being used for illustrations of, for example, a fossil of a jawbone, and red being used for the reconstruction of what the skull may have looked like.

The Making of Man started life as 'a book for young people explaining the theory of evolution', and soon became far too unwieldy, so was re-planned as a much shorter, illustrated text. I enjoyed I W Cornwall's description of the process:

"Two thirds had to be cut, first by taking out whole chapters and subjects, then whole paragraphs and sentences. It was still too big and, as a result of the cuts, scrappy and without cohesion. There had to be some new writing to draw the thing together again and then a final going over with the blue pencil. This was aimed at avoiding any repetitions, shortening sentences, taking out unnecessary qualifications of statements and finally removing even adjectives and trying to find short synonyms and substitutes for longer words in order to save a few letters."

The resulting text entirely avoids any of the 'teachery' condescension that crept into earlier non-fiction winners. It makes clear the limitations of the fossil record, and the fact that scientists are dealing with theories about which there are disagreements. Reading Rosemary Sutcliff I was thinking, 'Wow, four centuries is really quite a long time!' Then I read this in The Making of Man: ' . . . there was a huge gap of perhaps 20 million years between Proconsul and Australopithecus during which the fossil record was almost entirely blank.' Suddenly four centuries seems like the blink of an eye!

In his conclusion Cornwall points out that 'physically we are scarcely distinguishable, at least by our bare bones, from the later Old Stone Age men (of 50 to 100 thousand years ago).' That is to say, evolution takes place over a vast time-scale and we have no idea what will happen next. Evolution is also inexorable. It will happen, even though we are too caught up in time to see it. ''We, as individuals, are already so specialised, each in his own part of the work of our brittle civilisation, that most of the civilised survivors of some world-wide conflict or cataclysm would starve in a month or two, were the world to be plunged back into barbarism.'

Back in 1960 it was the threat of a nuclear holocaust that loomed large in everyone's minds. Now, perhaps, we see climate change as the greater threat, but Cornwall's final words are still relevant:

"Man now stands alone indeed, on a pinnacle of his own contriving, from which it would be only too easy for him to fall.

Life would still go on, only retreating a little to make another leap forward. The death of the dinosaurs might have seemed, to an observer gifted with reason but not foresighted, to be a disastrous destruction of the finest and most advanced creatures that nature could devise. We now know that their eclipse merely made room for the new experiment to begin, which has culminated in our own species. The 80 foot monsters with hen's-egg-sized brains could not have conceived of men. How, then, can we hope to imagine what sort of natural beings will take our places if—or, rather, when—homo sapiens becomes extinct? They will be different. That is all we know."

Like homo sapiens, non-fiction books can rapidly become out of date. Already, my 1966 edition of The Making of Man contains updates about new discoveries, but it remains worth reading, and it's a beautifully produced book, published by Dent, and of a similar quality to their Illustrated Children's Classics series.

Cornwall had 'never even heard' of the Carnegie Medal when he received the letter telling him he'd been awarded it. And he went to great lengths to make it clear that it wasn't 'mine alone, though the Medal bears only my name. It was the result of the closest collaboration throughout between publisher, author and artist.' It is 61 years since a non-fiction book last won the Carnegie Medal. Surely that's too long.

Originally published on ABBA May2021

Comments

Post a Comment