Divided Opinions—The God Beneath the Sea

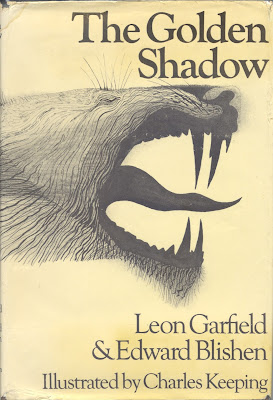

When I bought my copy of The God Beneath The Sea many years ago I did so because I loved the Charles Keeping illustrations and not because I was desperate to read this new interpretation of the Greek myths by Leon Garfield and Edward Blishen. I first read it thirty years ago and neither loved nor hated the text, but I was very glad that it had given Charles Keeping the opportunity to make those haunting images. I bought and read the sequel, The Golden Shadow, too, and the illustrations in that book are, for me, even more haunting. As the late, great, John Prine put it in his song Lake Marie—

'You know what blood looks like in a black and white video? Shadows, shadows. That's what it looks like.'

There are a LOT of shadows in Keeping's illustrations.

I was astonished, when I came to write this blog, to discover that this book, which won the Carnegie Medal in 1970, divided critical opinion more starkly than any previous winner had done. I thought I'd better re-read both books, and I'll describe that experience later, but what fascinates me most is the extraordinary controversy generated by the text, and particularly by the writing style. This is described in an unusually lengthy Wikipedia article, but tracing critical comments back to their sources was a cautionary experience, as in: you are unlikely to get the whole story from Wikipedia. Or from this blog post either, come to that. So here are extracts from some of those opinions.

'This neglected book is the best ever rendering of the Greek myths in modern English. Visceral, overpowering, defiantly undomesticated, it brings out as no other version does the ancient stories' potential for woe, wonder, transformation and astonishment.' Francis Spufford in The Guardian 30/11/2001

'These goings on . . . are made vividly new, interesting, often exciting . . . It is a real feat to make everything sound so first hand. These are in fact genuine imaginative retellings.' Ted Hughes in Children's Literature in Education, November 1970.

Philip Pullman said in an interview with Alex Sharkey that he was inspired to tell stories from the Greek myths to 12 and 13 year old pupils by The God Beneath the Sea. 'I loved the book and wanted to use it in class, but reading it aloud didn't work. So I made up my own version and told that.' Independent 6/12/1998.

'The authors have succeeded in attaining a literary style which breathes a robust vitality into the ancient myths and legends in a manner which, whilst not unique, is truly inspired.' Alec Ellis in Chosen for Children, 1977.

It sounds like a terrific book, doesn't it? Although there is that proviso in Philip Pullman's piece where he tells us that reading the stories aloud to pupils 'didn't work.' It's true that the immediacy of telling a story is especially effective where the stories originate from an oral tradition. But perhaps the key to why they didn't work as readings is contained in some of the more critical reviews.

In a piece in The Spectator in 1973 John Rowe Townsend said 'The authors were asking English prose to do something it has never been at ease with since the seventeenth century, and many reviewers thought that the Garfield/Blishen attempt at high flight ended like that of Icarus.' (That one, like the next, did come from Wikipedia I'm afraid.)

Rosemary Manning was one of the reviewers Townsend mentioned. In the TLS she described the writing as 'lush, meandering and self-indulgent.' 'Loaded with . . . lazy adjectives . . . and weighed down under laborious similes.'

But even more savage was Alan Garner's review in The New Statesman. This was reprinted, alongside the more positive Ted Hughes review, together with pieces by Edward Blishen and Charles Keeping in the November 1970 edition of Children's Literature in Education. Garner began by pointing out that the subject matter of these stories, which is extremely violent, is somehow deemed to be acceptable to offer to children because it is myth, not realism. You may remember that Garner's The Owl Service was criticised for its themes of illegitimacy, adultery, jealousy and revenge back in 1967. Here's how he begins his review:

'We live in strange times. A character in a story, with his mother's help, cuts off his father's genitals, has children by his own sister, and eats them at birth. This seems to be OK for a child to read. In a different story, 'bastard' and 'arse' occur, and a teacher sends a letter chiding the publisher for printing filth. The crucial difference between the stories is that the first is a myth and the second is a modern novel.'

Alan Garner makes the argument that this material is potentially explosive and needs to be carefully mediated if given to children. It needs to be done well. In his own piece in Children's Literature in Education Blishen makes the case for what he and Garfield have done:

Both Leon and I have for a long time been concerned with what seems to us to be something that's happening inside children's literature, and is happening inside society as a whole. We're no longer quite so sure what children are, or who children are, or when children are. We must all be aware that in the last few years children's literature has been moving, at its senior end, closer and closer to adult literature . . . We believe it was essential to go as far as we have in our treatment of human passion and of violence, of necessary cosmic violence. We felt this must be done, it was right to do it, because these are the themes, the concerns, the preoccupations with which our children are, we know, at the moment filled.

I have a problem with this. If we don't know who, what or when our children are I don't understand how we can be so sure about their concerns and preoccupations. Garner accepts, however, that it's good for an attempt to be made 'to restore Classical myth to its original vigour', but he does not like this attempt one little bit.

'With so many books published annually, and so little space available to a critic, it seems extravagant to pay attention to rubbish, but in this case there may be a lesson to be won from the experience. The God Beneath the Sea (Longman 35s) is very bad. It is almost impossible to read, let alone assess.' And then: 'Leon Garfield and Edward Blishen have fallen into the trap they tried to avoid. The prose is overblown Victoriana, 'fine' writing at its worst, cliché-ridden to the point of satire, falsely poetic, groaning with imagery and, among such a grandiloquent mess, intrusively colloquial at times.'

Is it possible that all these critics are discussing the same book? 'Almost impossible to read', says Garner, though I note that he most certainly did read it and he had no problem delivering his judgement. I took it as a challenge anyway, and managed to achieve the 'almost impossible' yesterday. My own assessment? I can't handle all those adjectives and similes, but you know, for some people it's poetic and powerful. The God Beneath the Sea would, for instance, provide perfect instructional material for teachers to use with children in Key Stage 2—those between the ages of 7 and 11—if it wasn't for that pesky subject matter. In fact it might almost have been written by a particularly imaginative and unrestrained 9-year-old who had been egged on by a teacher to indulge in 'WOW!' words and had just discovered the joy of creating unnecessary similes. But you couldn't use it with those children. Rape, child murder and incest are not on the menu in Primary schools, even today, thirty years on. The only justification I can think of for the way the book is written is that its 'over-the-topness' sort of feels in tune with its extreme subject matter, but the problem is you end up with a book written in a style well-calculated to appeal to a 10-year-old but with subject matter better suited, as Edward Blishen kind of suggests, to an almost-adult. And maybe that's why it didn't work for Philip Pullman's slightly older pupils.

The curious thing about this is that neither Edward Blishen or Leon Garfield are bad writers. They just seem to have got carried away and been, as Alan Garner notes, unrestrained by their editor. But maybe some of the criticism hit home because I believe that the sequel, The Golden Shadow, is a better book, written with greater restraint and more interestingly structured. Or, to put it another way, I enjoyed it a lot more.

|

| Prometheus from The God Beneath the Sea |

One of the challenges the authors faced was finding a way of linking the myths together in a continuous narrative. In the first book various myths were recounted by Thetis and Eurynome to Hephaestus after his first expulsion from Olympus. This works pretty well, but we never really feel anything for Thetis and Eurynome, a goddess and a nymph. What we need is a human perspective, and I certainly found this first book more engaging once Prometheus had created humans. In The Golden Shadow the link between the stories is provided by an ageing, itinerant storyteller with fading eyesight (Homer is never mentioned), whose dearest wish is that he might actually see one of the gods who people his stories. We feel his own uncertainty about whether his stories are true. He is constantly arriving on the scene of great events just a little too late and I for one, an ageing storyteller myself, felt a lot of sympathy for him.

|

| A suitor of Atalanta from The Golden Shadow |

I probably won't read either of these books again, but I will, for sure, take them off the shelf to look at the extraordinary drawings by Charles Keeping. Alan Garner suggested that anyone who bought The God Beneath the Sea should throw away the text and frame the illustrations, some of them, he said, 'more terrible and beautiful than Goya.' (He does seem to have got a little carried away in writing this review. The illustrations are perhaps not quite so good as he thinks, and the writing not quite so bad). Charles Keeping himself was in two minds, both about the Greek myths and about the finished illustrations for the first book.

'When I first met Leon Garfield he asked me would I like to join with him and Edward Blishen to do the Greek myths. And I thought 'My God, what a horrible idea.' Mainly because I did not like the Greek myths in any shape or form, but because I liked Leon I said 'Oh yes, Leon, I will.'

A friend provided Keeping with a copy of Robert Graves' The Greek Myths, which Garfield and Blishen were to use as the main basis for their work. His initial reaction was not favourable. ' . . . one of the worst things you can do when you're reading Graves' Greek myths is to read them from the beginning because every one seems to be almost identical. They seem to be the same old thing over and over again.'

He found the myths 'really quite disgusting at first' He commented on the fact that they were 'completely devoid of any love. This is all lust, rape, revenge and violence . . .' But gradually he started to find that 'many of the stories linked tremendously with the Bible and other stories that one knows from other cultures and other religions. It seemed to me that there were some basic human passions there which we could use.'

Now this is where, if you only read the Wikipedia page, you might well misunderstand what Keeping was trying to say. He was dissatisfied with many of the images he finally produced, but only, I think, in the way that any real artist is dissatisfied with their work, and he makes this clear. 'I produced a set of drawings much to my disgust not all awfully good. I think there are one or two—or three or four—which might be good. I don't know yet. I need a passage of time to tell . . . Whether I succeeded or not I don't know but I can tell you I'm looking forward to the next one we do together because I'm hoping to redeem some of the mistakes of the first one. If illustration wasn't about progressing from one stage to the next then it wouldn't be worth doing.'

|

| Heracles realises he has killed his own children from The Golden Shadow |

There is no doubt in my mind that Keeping succeeded triumphantly. The illustrations in The Golden Shadow are unforgettable.

Shadows and blood.

Originally published on ABBA December 2021

All illustrations are by Charles Keeping.

Comments

Post a Comment