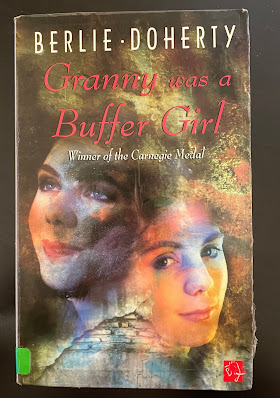

Berlie Doherty's Buffer Girls

Not many teen romances had won the Carnegie Medal before 1986, but that was the year Berlie Doherty won, somewhat to her surprise, with Granny was a Buffer Girl. She gave the world four love stories for the price of one, with added extras. This Mammoth edition is not the greatest. The book had its origins in a series of short stories that Doherty was asked to write for BBC Radio Sheffield and it was inspired by William Rothenstein's painting Buffer Girls in Graves Art Gallery in Sheffield. These stories were then later reworked into a novel. It's a short novel which begins as Jess, the central character and sometimes the narrator, is about to leave home for a year in France as part of her university course. Her family have gathered to celebrate the life of her brother, Danny. Danny has died some years earlier, at more or less the same age Jess is at the start of the book, though at first we're told very little about him. It's only later that we learn of his life co