The Carnegie Goes Global

I really didn't enjoy reading Josh, the winner of the 1971 Carnegie Medal. The story is told through the eyes, imagination and paranoia of Josh, the almost 14-year-old central character, and he is so annoying, so emotional, so given to over-reaction, that he makes for very uncomfortable company. This is not to say that it's a bad book. In fact it's unforgettable, but I wouldn't want to read it again. And I did try, because I found this enthusiastic review by John Dougherty from 2012 and I wondered if we'd read the same book. But it was no good. It just wasn't for me.

Ivan Southall was a major voice in children's literature in the 1960s and 1970s and his books for young adults were widely read. He was the first, and so far the only, Australian to win the Carnegie. After fighting in the RAF during WW2 he wrote a series of adventure stories about a daring pilot called Simon Black during the 1950s, before turning to realistic, character-driven tales of survival in the 1960s. There is a fascinating interview with Southall on ABC radio in which he talks about his habit of reading everything he writes aloud, and about his long experience of telling Bible stories in Sunday Schools. His prose, perhaps partly as a result of this, is rhythmic, powerful and at times poetic, but I've read three of his books now, and I haven't found a single character I liked in them, so I wasn't surprised to hear him describe in the same interview something his eldest daughter had said to him:

"Here's my father, the Pied Piper of half the kids in the world, he doesn't understand his own children." "This was a fair comment," Southall adds. Southall's 'problematic' relationship with his daughters is mentioned in a paper by Australian academic, John Gough, and I was struck by a comment of Southall's which was quoted by John Rowe Townsend in Written for Children. Describing the moment when he decided to turn from tales of derring-do to novels of character he says this:

'For the first time, I found myself looking at my own children and their friends growing up round about me. In their lives interacting one upon the other at an unknown depth, I began to suspect with genuine astonishment that here lay an unlimited source of raw material far more exciting than the theme itself [for a novel which had occurred to him]. Thus there came positive moment of decision for me.'

I'm not sure that Southall ever really understood those 'unknown depths' in his children and their friends, but Josh is different from the novels about children surviving in terrible circumstances that preceded it, for it's based in great part on Southall's own childhood experiences.

In the book, Josh takes a train journey from the city to go and stay with his Aunt Clara in the very small town of Ryan Creek where his ancestors were pioneers. Going to stay with Aunt Clara is a rite of passage in his family. 'Until you see Aunt Clara, Josh, gee, you haven't lived,' is what all his cousins say, though his dad says Ryan Creek is 'dead as a doornail,' and his mum tries to persuade him not to go, saying Aunt Clara 'can be very strange.'

Josh is a sensitive boy who writes poetry. He seems to be almost notorious for this, for his aunt has already heard about it and by the time Josh wakes up after his first disastrous night in Ryan Creek his aunt has not only read the poetry, but told everyone in the town about it. (One wonders why he took the book with him if he didn't want anyone to see it.) Thereafter Josh takes just about everything anyone says to him the wrong way. His feelings, his misery and resentment, are so intense that it's easy to believe they might have been Southall's own feelings as a boy.

I did want to like Josh. Its author clearly cared deeply about the book. Talking about his memories of his Aunt Clara he says it was 'so long ago that memories and fiction must be a little mixed, remembering Aunt Clara for what she gave me to keep for myself.' 'For years I struggled to write the book,' he says, but then, after many failed attempts, 'came Josh - up came that skinny kid from somewhere out of the mists . . . He possessed me, I think. Spoke his own language, did his own thing, and I knew he was something that had not happened before in my life. He's the spirit of some of the nice things I like about kids, and the silly things, and the funny things, and the sweet anguish of growing up.'

There is a series of misunderstandings, to put it mildly, between Josh and the local kids. Unfortunately Josh is not someone who can take a joke. One of the clever things about the writing is that even though the actions and speech of the other kids are filtered through Josh's perception, we can still see them for what they are. And humour is an issue in the book, an issue which is addressed directly in the text:

'It's just that everything I do goes haywire.' [says Josh]

'Well I did say, didn't I, that you take things rather seriously. I think you take them too seriously.'

'But I don't.' Beating around trying to find the words he wanted. 'Honest, I'm trying to see the funny side all the time. I always do, Aunt Clara, whether you believe it or not.'

'You say some funny things, Josh, but that's not quite the same.

'I don't know what you mean . . .'

'I think you do. Comedy can be a very serious business for you, and for other people like you; that doesn't mean you're lighthearted. When I talk about sunshine, Josh, it's sunshine that I mean. Laughing on the outside, but crying on the inside I don't mean that at all.'

Well, Josh doesn't get it. And it's a big problem for the reader, or for this reader. We spend the whole book in Josh's head, and Josh doesn't find anything funny, especially where it concerns himself. So, as a reader, I didn't find any of it funny either. It was, as Josh himself describes it, 'a pit of melancholy.'

I thought I'd better read some more by Ivan Southall, so I tried To The Wild Sky, a 1967 novel about a group of teenagers who are travelling to a birthday party in a small aircraft when the pilot has a heart attack and dies. Once again, despite a lot of brilliant action sequences, I didn't like any of the characters. It struck me that all of their emotions were dialled up to 11 all the time, so that even before they got on the plane to go to this party there was wailing and crying and arguing and agonising. This is perhaps why, during all the hours of nail biting flying before they crash-land, some of the kids simply sleep. It's as though their emotions are already wound up so tightly there is nowhere else for them to go. And meanwhile the oldest boy, Gerald, whose party it is, pilots the plane. Ivan Southall piloted flying boats during the war so that aspect of the book is utterly convincing.

For fifty pages there is almost no dialogue, it's just what's happening inside Gerald's head as he struggles with the terrifying situation, but it seems to me that in trying to be realistic in his depiction of character, Southall amplifies the negative aspects of the children's personalities to such an extent that they are completely out of balance. You might expect to be sympathetic towards Gerald, a fourteen-year-old boy suddenly responsible for the lives of five children, trying his best to fly a plane to safety when he's never piloted a plane on his own, and barely knows what to do. But somehow Gerald is just as annoying once he's landed the plane as he was before they all got into it. I think Daphne Fisher got it right when she pointed out in her review in the Canberra Times that 'one is left with the feeling that the characters of the children themselves has not been altered. Strengths and weaknesses have been highlighted but underlying patterns of behaviour are seen to have emerged unscathed.' Don't ask about 'character arcs'. There are none.

The same reviewer suggested that the book 'ends hopefully', but I thought the prospects for the children looked pretty grim, despite one of them managing to make fire. The book leaves them on a deserted beach on a deserted and possibly disease-ridden island with no food, water or shelter, a thousand miles from where anyone would expect them to be, so I didn't feel too hopeful myself. There was, in fact, a sequel published many years later in 1984, partly prompted by readers' requests to know what happened next. I didn't find A City Out of Sight any easier to read than the others.

After all this reading I was almost relieved to find John Rowe Townsend's take on Ivan Southall in Written for Children: 'To the Wild Sky and Finn's Folly in particular are harrowing books which appear to force a confrontation; to demand of the reader how much punishment he can take.' And here is what he says about Josh; 'The taste remaining the mouth is of bitterness and alienation. In his books of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Southall seems to have been less and less concerned to make a positive appeal to young readers; they can take his books or leave them. Those who can take them may find them quite an experience.'

These are my feelings exactly but, as I said at the beginning, others feel very differently. I'd like to suggest you judge for yourselves, but only a very few of Ivan Southall's books are available today, and those only as Kindle editions. Most are long out of print. It does seem a shame there is no arrangement to keep Carnegie Medal winners in print, as is generally done with Newbery Medal winners in the USA. Ivan Southall's was a new brand of realism in children's literature and may well have opened a new direction for future writers. If anyone would like a copy of Josh please tell me, as I have two - a result of my inability to resist Puffins in charity shops. And fortunately most of Ivan Southall's books were very popular in their time, so second-hand copies are fairly easy to find on the Internet.

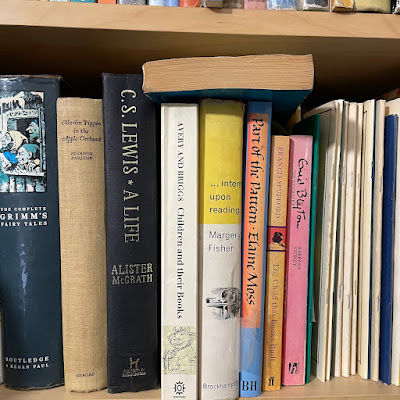

I only have one copy of John Rowe Townsend's excellent survey of children's literature, and I wish I had half a dozen, because every time I want to refer to it I can't find it.

|

| How NOT to file a book you want to be able to find! |

Originally published on ABBA Jan 6th 2022

Comments

Post a Comment