The Strange Case of William Mayne

My reading of Carnegie Medal winning books has brought me to 1957 and to the strange case of William Mayne, whose novel, A Grass Rope, won the prize that year. For reasons that I’ll explore later Mayne was considered one of the most important children’s authors of the second half of the twentieth century. He also became perhaps the most notorious, after his conviction in 2004 for a series of sexual assaults on young girls between the ages of 8 and 16, dating back to the early 1960s. He was sentenced to 2½ years in prison and eventually died in 2010, aged 82.

Julia Eccleshare notes, in her Guardian obituary, that Mayne's books were ‘largely deliberately removed from library shelves following his conviction,’ and a quick check of my local library’s catalogue reveals that only one of his books is currently available to borrow, out of approximately 100 that he wrote. Whether very many of those books would still be on the shelves even had he not been convicted is doubtful. Mayne was a famously ‘difficult’ writer and it was said that his books were more often read by adults than by children.

Whether or not we believe that William Mayne's books should be read by today's children, it is impossible to ignore his influence on children's literature. One of the most absorbing aspects of my trawl through the Carnegie winners has been the gradual appreciation of the way each emerging author depends on those who came before, and the path from William Mayne to my own writing could not be clearer. I wrote, in one of my earliest posts on this blog, that it was because of Jan Mark I became a children’s author. I said of her book, Handles, ‘I wish I had written it.’ What a surprise, then, to pick up a copy of Mayne’s A Swarm in May and find this quote from Jan Mark on the back cover: ‘I read it and re-read it. I wished I had written it.’

|

| Chapter heading by C Walter Hodges |

Charles Sarland, writing in Signal (Issue 18), provides the most succinct summary I’ve come across of the key features of A Swarm in May: ‘the meticulously detailed descriptions of the physical environment; the uncanny insight into a small boy’s concerns; and the wordplay, the witty allusions and puns that inform the book.’ Substitute ‘child’ for ‘boy’ and these three attributes are found in every book I’ve read by William Mayne, but A Swarm in May is a tour-de-force. It is a book full of sound and music, especially organ music. It begins in the silence of an empty street in a cathedral town at dusk and ends with a triumphant metaphor of the cathedral organ as a ‘sea-storm of sound as Dr Sunderland built and rebuilt enormous endeavours and sent out convoys of melodies, only to wreck them on rocks of harmony, and beat them down with wind and waves.’ Until, finally: ‘In the midday Cathedral there was peace under the echoes.’

|

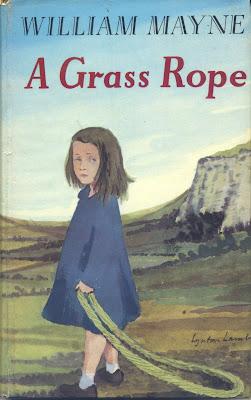

| Original cover by Lynton Lamb |

A Swarm in May didn’t win the Carnegie in 1955, losing out to Eleanor Farjeon’s The Little Book Room, but in 1957 Mayne was finally recognised for A Grass Rope. It’s set in a remote village in the Yorkshire Dales, where a local legend tells of the lost hounds of Thoradale, imprisoned in a cave with treasure attached to their collars, and of a unicorn brought back from the crusades. The children in the story are descendants of the lovers in the legend, and the dog that lives at the Unicorn pub is a descendant of the hounds. Adam, head-boy of the grammar school and a relation of the family who keep the pub, is determined to use reason and science to solve the mystery of what happened to the hounds and find the treasure, but Mary, some years younger than the other children, believes that the hounds and the unicorn are imprisoned by magic, and that by weaving a rope of grass she will be able to catch the unicorn and solve the mystery.

In this use of legend, as well as in the use of the Yorkshire vernacular, it seems to me there's a clear link to the work of Alan Garner. Here’s Charley, the farm labourer; 'It’s downhill,’ said Charley. ‘But tha’d best walk. Lew bank is nowt. T’other side, into Vendale, is wicked. Yowncorn Screw, they call it, after Yowncorn Yat yonder. Very nigh as steep, too.’

And here’s Gowther Mossock in The Moon of Gomrath: ‘But if you’re set on going, you mun go – though I doubt you’ll find much. And think on you come straight home; it’ll be dark in an hour and them woods are treacherous at neet. You could be down a mine hole soon as wink.’

|

| Cover designs by George Adamson |

I think Mayne does this kind of thing far better than Garner does in his early books, (Garner himself ‘regrets his earlier attempts to reproduce dialect’ according to Neil Philip) but Garner, as it were, picks up the ball and runs with it, so that by the time of The Stone Book Quartet there’s no need any more for the phonetic spellings. It’s all in the rhythms of the speech, the precision of the vocabulary and the poetry of the natural language. In the same way, Garner develops the use of myth and legend over the years. In the early novels it’s fairly straightforward – two ordinary children drawn into a world of magic. But by the time of The Owl Service we see a group of teenagers doomed to repeat an ancient love triangle which has been played out in a remote Welsh valley for generations. And in Red Shift the legend of Tam Lin on which the book is based is never explicitly referenced at all.

|

| Jacket illustration by Michael Foreman |

I’d argue that A Grass Rope is a much more subtle piece of work than, say, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen because Mayne leaves it to the reader to determine whether magic or reason has solved the mystery of the hounds and the unicorn, and Mayne’s characters, all of them, are beautifully drawn; none better than little Mary who weaves the grass rope and discovers the secret of the hounds. This is Mary helping Charley fell a small tree for a fence-post:

‘The chipped wood was white, veined with red. The chips were sticky and smelt like snow. Mary warmed a piece in her hand and smelt it again; but the scent had changed to dry moss . . . Mary took the axe and put the hot sticky blade against her cheek. The steel smelt like a knife that has cut an apple.’

Mostly, we see the world from Mary’s point of view. All the sounds and smells and tastes are are as fresh as if they were being experienced for the first time. Mary is clever and idiosyncratic, but her parents are almost a match for her.

‘Can I keep a fox if I find one?’

‘You’re not to find one,’ said Mother, because if she said yes Mary would bring in any sort of animal instead and leave it in the kitchen and say it would do instead of a fox; if Mother said no, Mary would do the same and point out that it wasn’t a fox.

And now, just for fun, here are the openings of three novels: A Grass Rope; Jan Mark’s Thunder and Lightnings, and my own Green Fingers – the only one of the three not to win the Carnegie, though it did get on the long-list. Ah well . . .

Nan passed eggs out one by one to Mary, who put them in the basket. One hen was sitting lazily in a nesting box in the warm sunlight. Nan pulled her out and sent her off in a cloud of chaff and feather dust and warm hen smell. (A Grass Rope)

|

| Jacket illustration by Jim Russell |

When the car stopped Andrew was the first to get out.

Since they left the old house, four hours ago, he had been trapped in the back, wedged between the carry-cot and the guinea-pig hutch. On one side Edward growled to himself in the carry-cot and on the other the guinea-pigs whistled fretfully. (Thunder and Lightnings)

|

| Illustration from Green Fingers by Sian Bailey |

Kate and Mike sat in the back of the car. Emily was wedged between them, fast asleep, with her dirty old bit of sheet grasped tightly in her hand. Mum and Dad were arguing as usual. Kate stared at the house through the patch she had cleared in the steamed-up window. (Green Fingers)

Oh, yes, just one other thing. William Mayne famously preferred not to use any speech attribution other than said. Jan Mark also sticks with said most of the time in her two Carnegie-winning books. In my experience editors do not like this approach and are only too happy to vary your speech attributions for you - if you give them the chance.

We can remove William Mayne's books from library shelves, but there is no denying that many writers owe him a debt, myself among them. And you might enjoy his take on writing a book:

'There is nothing particularly interesting in writing a book. In fact, it is rather a bore for everyone, and generally spoils the idea that was there in the first place.'

From An Awfully Big Blog Adventure. March 2021

Comments

Post a Comment