A Gorilla in the Garden

Many years before Anthony Browne began his wonderful love affair with gorillas and other apes, Lucy M Boston produced a passionate, moving and surprising novel about an escaped gorilla finding refuge in the garden of Green Knowe, her lightly-fictionalised ancient home on the edge of the fens. The real house is The Manor at Hemingford Grey in Cambridgeshire, and you can visit the house and garden.

If you haven't read A Stranger at Green Knowe yet (it won the Carnegie Medal in 1961), here is your spoiler alert. I can't really say what I want to say without revealing the ending.

The first section of the book is written from the point of view of the young gorilla, describing its everyday life as a member of a family of gorillas in the wild. I can't say how accurate it is, but I found it completely convincing. It is also genuinely frightening as a ring of hunters closes in on the gorillas, killing most of them and capturing one, whom they name 'Hanno'. Anthony Browne doesn't mention A Stranger at Green Knowe in his account of how he came to create his picture book Gorilla, but he did name the little girl who is the protagonist of his story Hannah, which is quite a neat coincidence.

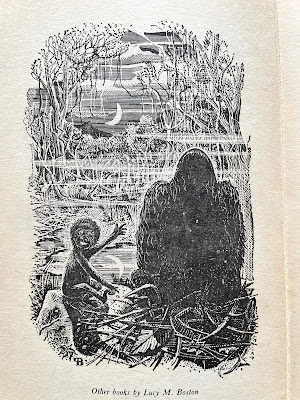

|

| Illustration by Peter Boston |

From the African bush we cut to London Zoo, where the young Chinese refugee, Ping, who has appeared already in The River at Green Knowe, is transfixed by the sight of Hanno in his cage. Like Hanno's, all Ping's family have been killed and he's been confined in places very like prisons, a parallel which is brilliantly brought out by the image of concrete. Ping sees Hanno constrained by his cage:

'The cage was just big enough for him to take a bound from corner to corner, or he could stretch to his full height on the platform and touch the ceiling. It was as if Ping were shut up for life in a bathroom. The walls were tiled and the floor concrete. He had a horror of concrete. It was one of his nightmares. He had lived on it in refugee camps that were often warehouses or railway sheds. That was where he had come to know and loathe it. It was either deathly cold or mercilessly hot and had a hateful feeling under one's fingers, like rust. Every time his hands or the soles of his feet came in contact with it, they remembered the warm boulders, the live turf, the leafy forest tracks . . .'

Ping is invited to stay for the holidays at Green Knowe, and then Hanno escapes from the zoo and stows away on a truck returning to the fens from Covent Garden market. On a small island attached to the Green Knowe garden by a narrow bridge, Hanno finds a refuge among Mrs Oldknow's bamboo thickets, and it's there that Ping finds him, and has the wonderful, if scary, experience of taking on the rôle, first of the gorilla's keeper, and then of his child for a few days, as the hunt closes in. (Anthony Browne has a great and scary story about his own first encounter with a live gorilla. See below for the reference.)

As the book reaches its climax Hanno sees Ping threatened by a maddened cow and intervenes to save the boy. Then he sees in front of him the man who killed his father and his family — Major Blair, the animal collector and gorilla 'expert' who's been called in to help the hunt. Hanno charges, and is killed. Lucy Boston says that she makes her gorilla 'choose the risk of death over captivity', and that this is the most anthropomorphic thing she makes him do. She goes on to say that 'this is something that countless animals have done. Often when caged they simply cease to live, though with all the material necessities of life around them.' Disputing the idea that it is 'the knowledge of the certainty of death,' that separates men from the animals, she says '. . . animals fear it, and every moment of their lives they take action to avoid it. They know it when they see it and howl for their dead. What child of five believes in death more than that, or who but the rarest of us, after sixty years of consciously trying, can accept the impossible concept; Death means me'?'

This mention of 'a child of five' references Boston's earlier statement, and, again, I don't know how true this is, that 'in mental development a young gorilla brought up in a human family outstrips a child in intelligence up to the age of five.' She makes clear her intention in the book: to show children that 'a world in which all living things are sentient is of course even more painful to consider than one in which mysteriously only we suffer. But it has also the grandeur and comfort of a comprehensible wholeness to which a total response is possible.'

This all makes the book sound very serious, which it is. But it's also a tremendous read. I was apprehensive when I came to it because I'd just read The Children of Green Knowe for the first time, and I'd been a little disappointed. After a terrific start, with its description of a small boy arriving at Green Knowe through a flooded landscape, the supernatural elements of the story didn't really grip me and the climax was not as strong as it might have been. But of course, The Children of Green Knowe was Lucy Boston's first children's book, written when she was only 62. She was 69 when she won the Carnegie Medal with A Stranger at Green Knowe and had learned a thing or two.

You might think that a 69-year-old winner would have attracted some awe and respect from the Library Association who had, after all, bestowed the award on her. Not so! Lucy Boston describes the shoddy treatment she received in her book Memory in a House, in a chapter called 'A Snub to Success'. After taking lessons in public speaking and memorising her twenty-minute speech she took a long train journey to Llandudno where she was put up by the Library Association in a very shabby hotel (no curtains in her room!), only to discover on the day of the conference that no speech was required. 'She was made to feel 'unwelcome and unimportant.' I learned about this from Ruth Allen's excellent book about children's book awards, Winning Books, in which she says: 'Mrs Boston's experience, and her vivid account of it, has gone down in the annals of children's librarians ever since.'

I've now been reading these Carnegie Medal winners for more than a year, and I've managed 24 so far. Some of them I've struggled to finish, but then along comes a book like A Stranger at Green Knowe that is completely absorbing and that I will definitely read again. I'll also read the rest of Lucy Boston's books, and visit her house and look at her remarkable patchwork quilts. Books like this make the whole project worthwhile. I started because I knew there were writers on the list I had never read, and some I'd never heard of. There are more than 50 still to go, though I've yet to decide whether to re-read some of them that I know well, and I'm hoping that the exciting surprises will continue to outweigh the disappointments.

Anthony Browne (with Joe Browne) talks about Gorilla and many other things in Playing the Shape Game, Doubleday, 2011

Originally published on ABBA June 2021

Comments

Post a Comment