The Carnegie from the Beginning March 2020

I’ve just started on a project that’s been in my mind ever since a friend in the Schools Library Service showed me a shelf in their offices containing all of the Carnegie medal winning books. I’ve started reading them all, from the beginning.

I thought I ought to do this partly because there are quite a few names on the list that I had never heard of, to my shame. I'm not sure if this will be an occasional series or a monthly one, but this month I’ve read the first three winners.

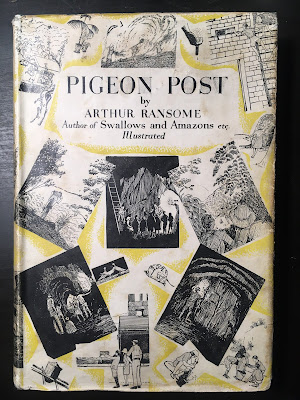

PIGEON POST (1936) by Arthur Ransome is the book of which his wife, Evgenia, said ‘it’s not very much worse than the worst of the others.’ She also told him, later that year, that WE DIDN’T MEAN TO GO TO SEA was ‘flat, not interesting, not amusing.’ Luckily for Ransome, hers was not the only opinion he listened to. However, it’s probably fair to say that PIGEON POST is not Ransome’s most successful book, and it was said that it won the inaugural Carnegie partly in recognition of the achievements of the Swallows and Amazons series as a whole.

I remember enjoying the book as a child, and re-reading it now it strikes me just how important is Ransome’s ability to produce a vivid sense of place. He loved the Lake District and he knew and loved its people, who spring brilliantly to life on the pages of the book—station porters, farmers and their families, an elderly slate miner. But the plot feels forced at times.

I think this is partly because Ransome is very aware that Nancy Blackett, the chief inventor of the make-belief transformations of the real world around them that drive the early books so successfully, is now getting a little too old for this. And, indeed, the younger children notice in this book that at times the older ones are acting ‘almost like natives’. For me the most interesting thing about PIGEON POST is the treatment of Titty’s terror and distress when she finds that she, alone of the children, is able to dowse for water with a forked hazel stick. Ransome gives her an inner life of a quite different order and complexity to any of his other characters.

Eve Garnett’s THE FAMILY AT ONE END STREET, which won the prize in 1937, was written quite deliberately to counterbalance the overwhelming preponderance of middle-class children in children’s fiction, and in books like PIGEON POST. Garnett was a painter and illustrator who was commissioned to make drawings for Evelyn Sharp’s 1927 book THE LONDON CHILD. Garnett was horrified by the conditions she found ‘in the poorer quarters of the world’s richest city’ and THE FAMILY AT ONE END STREET was part of her effort to do something about this.

I hadn’t read this book before and was surprised to find that it is at least as much about the adults as about the children. It’s very entertaining and beautifully written, and I love the way the children seem to be completely trusting of most of the adults they meet, happy to hop into a car with them to go to a party or let them buy them a boat ride. In fact almost everybody seems to be terribly kind to almost everyone else, apart from the nosy neighbour two doors down and a bunch of French sailors who are understandably angry when a small boy nearly kills himself stowing away on their ship. Even the posh people are very kind to the poor people. It seems from the perspective of 2020 a very innocent world where people are happy even when they are hungry, and I wonder if Eve Garnett felt that there were some things that just couldn’t go into a book she intended for a young audience.

George Brown, the Labour politician, grew up in the East End of London, and in his autobiography he says ‘it was a happy childhood, with a wonderful spirit of equality among the people of our neighbourhood.’ This is what Eve Garnett captures so well, but George Brown also describes the time after his father was sacked for his part in the General Strike of 1926: ‘Every Friday I had to go to the workhouse with a little sack to collect our allotment of bread and treacle. I was bitterly ashamed and bitterly angry.’ This is what we don’t see in THE FAMILY AT ONE END STREET.

Many publishers turned it down, saying that they thought it 'not suitable for the young'. I think they found the depiction of working-class life shocking, even though the incidents with child protagonists are insightful and funny. It’s certainly very different from Arthur Ransome though it shares with Ransome's book the distinction of never having been out of print.

|

| From IS IT WELL WITH THE CHILD? |

Eve Garnett also produced a book of drawings of children in 1938. In this she illustrates snatches of dialogue and anecdotes sent to her from around the country. She also painted a 40-foot long mural in the Children’s House in Bow which shows children being led out of East End poverty into the green countryside. There’s a web page with pictures of the mural, which is badly in need of conservation and looking for donations!

And on to 1938. This year’s winner was THE CIRCUS IS COMING by Noel Streatfeild. Streatfeild was a giant of twentieth century children's literature, even though, at the beginning, she saw her children's books as a sideline and maybe even a distraction from the adult novels which she continued to write throughout her long career. Her first book, BALLET SHOES, was a runaway success. Streatfeild writes of passing a bookshop in Oxford Street where 'a sight met my eyes which astounded me. One entire window was given up to piles of my book, and around the window like a frieze hung pink ballet shoes.' My 93-year-old mother, whose memory is in tatters, saw me reading Angela Bull's biography of Streatfeild and instantly recalled being eleven years old and desperate to read the book.

THE CIRCUS IS COMING was Noel Streatfeild's third book for children, written after intensive research which involved travelling around Britain with Bertram Mills's circus. The opening sentence is hard to beat: ‘Peter and Santa were orphans.’ (It's the plainspokenness I admire, the desire to get on with it.) The children have been brought up by their Aunt Rebecca who, having been lady’s maid to a duchess, thinks that she knows the correct way to bring up children (the duchess’s way) This results in the children being very ignorant. They have never met many people either, certainly not ordinary people. Then their aunt dies and, rather than allow themselves to be sent to separate orphanages, they run away to try to find their Uncle Gus, who is a circus clown and an acrobat.

THE CIRCUS IS COMING was Noel Streatfeild's third book for children, written after intensive research which involved travelling around Britain with Bertram Mills's circus. The opening sentence is hard to beat: ‘Peter and Santa were orphans.’ (It's the plainspokenness I admire, the desire to get on with it.) The children have been brought up by their Aunt Rebecca who, having been lady’s maid to a duchess, thinks that she knows the correct way to bring up children (the duchess’s way) This results in the children being very ignorant. They have never met many people either, certainly not ordinary people. Then their aunt dies and, rather than allow themselves to be sent to separate orphanages, they run away to try to find their Uncle Gus, who is a circus clown and an acrobat.

They arrive in London and sit on a step to wait for a pawnbroker to open so they can get some money. They are saved by a man named Bill who takes them in, feeds them, and puts them on the right train. He tells them: ‘I’m taking a chance on you two . . .’ There’s no suggestion at all that they might be taking a chance on him. In 1930’s Britain it was the child’s duty to be polite to strangers, not run a mile. Or so it seems from these books.

Uncle Gus is a far more fully-realised adult character than is normally found in children's fiction, and I was surprised to find myself being invited to see inside his head. Perhaps it's the adult novelist being as interested in this adult as she is in the children, but unlike with the Eve Garnett book there is no doubt whatsoever that this is a book written for children.

There’s some wonderful stuff here about the children’s ridiculous prejudices being challenged and undone, some of it very relevant today. For example, it turns out all the circus children from Germany, Russia and France can speak AT LEAST two languages, and even though they go to school in a different town each week they are way ahead of Peter and Santa.

There’s some wonderful stuff here about the children’s ridiculous prejudices being challenged and undone, some of it very relevant today. For example, it turns out all the circus children from Germany, Russia and France can speak AT LEAST two languages, and even though they go to school in a different town each week they are way ahead of Peter and Santa.

The descriptions of circus life are fabulous, and the different ways in which Peter and Santa came to terms with their new life were absorbing and really well done. I especially liked the end of the book, and I’d say that the final paragraph is one of my top three ever. An excellent first sentence, a brilliant final paragraph and great writing all the way through.

Angela Bull's excellent biography has this story from Noel Streatfeild's schooldays at a rather staid Ladies College, which tells you a lot about her. Noel had started a class magazine WITHOUT PERMISSION.

‘She was summoned to the headmistress’s study, where Miss Bishop tore the precious magazine to shreds and forbade her to write another issue. This searing injustice provoked Noel to her worst act of defiance. She invented the Little Grey Bows Society.

The aim of the society was to be rude to the teachers. Every girl who joined got a little grey bow as a membership badge, and was awarded a hundred marks, one of which was docked each time she was polite in class. It was intended that the person with them most marks left at the end of term should win a prize.’

It ended badly, of course, and Noel’s parents were asked to remove her from the school.

Still, she had the last laugh. And I cannot resist including this little gem from Angela Bull's book. Having become, according to one critic, a classic in her own lifetime,' friends noticed her tendency at parties to begin every remark, 'Of course, speaking as a writer—'

PIGEON POST and THE FAMILY AT ONE END STREET are still in print, but THE CIRCUS IS COMING, rather surprisingly, is not. Angela Bull's very lively biography is readily available second-hand.

PIGEON POST and THE FAMILY AT ONE END STREET are still in print, but THE CIRCUS IS COMING, rather surprisingly, is not. Angela Bull's very lively biography is readily available second-hand.

Next month: Eleanor Doorly, Kitty Barne and Mary Treadgold.

This post was originally published on An Awfully Big Blog Adventure.

Comments

Post a Comment